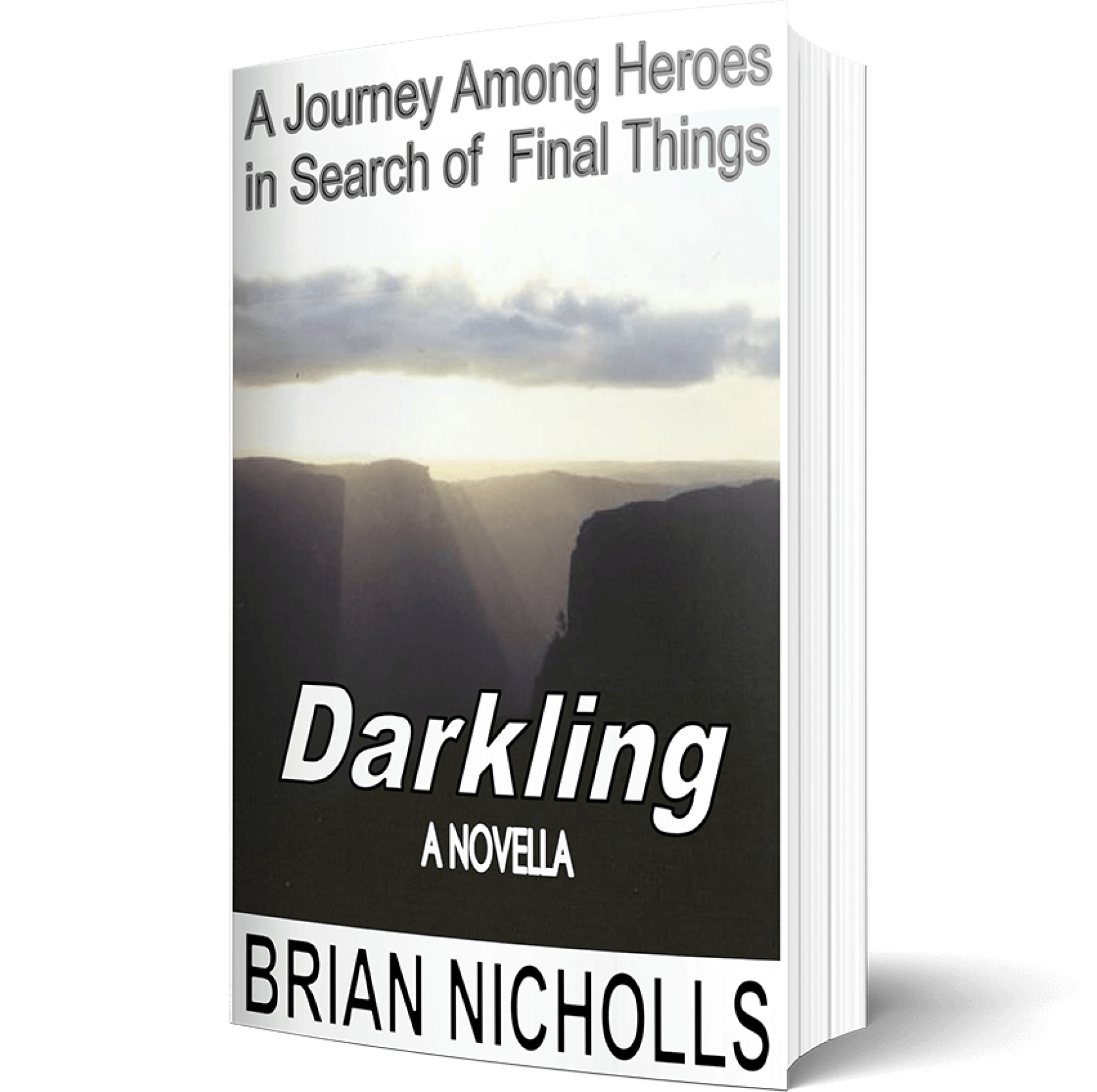

Darkling

A Journey Among Heroes in Search of Final Things.

George Brent is a soul in turmoil. Determined to avoid decrepitude he becomes obsessed with the idea of death. On a plane bound for London he reveals to a stranger-confidant a plan that is calculated and rational yet filled with poetic imagination. He becomes a knight-errant believing his death is the last remarkable thing that will happen to him.

Although he attempts to withdraw from things of love and affection, paradoxically, to carry out his plan he needs to rekindle his spirit. This he does with recourse to the wisdom of his heroes and the inspiration of a woman and a child.

Darkling is a confessional novella written in the style of the French absurdist author Albert Camus' The Fall and pays homage to the English explorer Sir Richard Burton, the French essayist Michel de Montaigne, the English poet John Keats, the German author Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius.

At the heart of Darkling are some of the big and small questions about dying – and living.

The Last Great Taboo

Monica Dennison

Darkling; A Journey among Heroes in Search of Final Things

A novella by Brian Nicholls

This is not a comfortable book to read for it concerns a sick man contemplating his end.

The author does not hide his intent. Faced with his doctor's daunting prognosis George Brent confronts the reader and a fellow passenger on a flight to Europe with all the unease, torment and indecision that might attend any person as they contemplate their last days.

As a subject of conversation death is still a great taboo. Thus to take on this subject for which we have created endless euphemisms is to be admired. While some as they get older come to terms with death and, indeed, like Keats, one of George Brent's heroes, may become 'half in love with easeful death'. On this journey towards his impending death Brent swings between the nihilism of Camus, the stoicism of Marcus Aurelius and the possibility that beyond death is not mere nothingness but some kind of easeful eternity.

In this quest to attach meaning to this process Brent broaches the possibility of God. 'Do I believe in God?' he asks. He equivocates and his answer, such as it is, becomes a little lost as he is distracted by a sally into Dante's Divine Comedy where, he notes, suicide is considered a sin.

Brent also toys with the Kubler-Ross delineation of the processes we experience in grief: the depression, rejection and acceptance. If nothing else, this man's journey illustrates the impossibility of fitting any one person's experience into neat categories.

The author couches these great themes in a slim volume that uses the device of a conversation with a fellow passenger on a flight to Europe where the reader is early on made aware that Brent is contemplating some kind of planned denouement with respect to these final things. Brent is aware that he must appear overwhelming, rather fractious and hardly full of the bonhomie that one might hope for of a fellow passenger. Nonetheless, rather in the manner of the Ancient Mariner and the unwilling wedding guest, Larry, the fellow passenger, is held in some kind of thrall until the story is told.

I would have preferred a straightforward conversation but the author has chosen to tell the account solely from Brent's point of view, making remarks like , 'Oh, so you think so and so,' and 'Yes. I agree, that's a good question'. We never hear Larry speaking directly. To me this is unnecessarily clumsy and it is only when we get to about a quarter of the way through the book that we hear less of this kind of 'echo' of what Larry says as Brent takes up the telling of his story in a more coherent way.

The heroes among who he walks are notably Camus, Keats, Marcus Aurelius, Montaigne, but also include Lawrence Durrell and Rousseau – the list goes on – with the odd nod to thoughts of others like Kubler-Ross.

He doesn't so much tilt at these heroes as seek the thoughts that best fit his state of mind. Perhaps to his fellow passenger's surprise, he, after some time, confesses a need to believe in something (p.70).

Though so fractious at first, the author deftly manages to elicit sympathy from the reader for this man's courage in facing death and in sharing with the reader all the hoops he has forced himself to jump through in working towards the fulfilment of his plans to be in control of as much of the remainder of his life as he can.

Many readers too will sympathise with his confession that 'for most of my life I seem to have been searching for something.' He longs for his spirit to be brought to life. The dynamic of the book lies in this quest that takes the reader not only through his literary heroes but canvasses the possibility of some rekindling of his love of a woman.

For those readers also 'in search of final things' this book will provide plenty of food for thought and perchance some spur to courage in facing the inevitability of death.

ISAA REVIEW Volume 12 Number 2 2013